Freeskycd driver win7. Oct 13, 2016 The English language was brought to Britain by Germanic. Accents therefore do not change as readily as. Peter Trudgill, The Dialects of. English Accents and Dialects is an essential guide to the varieties of. Arthur Hughes, Peter Trudgill, Dominic Watt No. English Accents & Dialects. Buy English Accents and Dialects. English accents and dialects: an introduction to social and regional varieties of British English. Arthur Hughes, Peter Trudgill Snippet view - 1979. A Guide to Varieties of Standard English Peter Trudgill, Jean Hannah, Professor of Sociolinguistics Peter Trudgill No preview available - 2002.

| Culture of England |

|---|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Part of a series on |

| The English language |

|---|

| Topics |

| Advanced topics |

| Phonology |

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

| Higher category:Language |

The English language spoken and written in England encompasses a diverse range of accents and dialects. The dialect forms part of the broader British English, along with other varieties in the United Kingdom. Terms used to refer to the English language spoken and written in England include: English English,[1][2]Anglo-English[3][4] and British English in England.

The related term 'British English' has many ambiguities and tensions in the word 'British' so can be used and interpreted multiple ways,[5] but is usually reserved to describe the features common to English English, Welsh English and Scottish English (England, Wales and Scotland are the three traditional countries on the island of Great Britain; the main dialect of the fourth country of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, is Ulster English, which is generally considered a dialect of Hiberno-English).

- 6East Anglia

- 7Midlands

- 8Northern England

General features[edit]

There are many different accents and dialects throughout England and people are often very proud of their local accent or dialect. However, accents and dialects also highlight social class differences, rivalries or other associated prejudices—as illustrated by George Bernard Shaw's comment:

| “ | It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.[6] | ” |

As well as pride in one's accent, there is also stigma placed on many traditional working class dialects. In his work on the dialect of Bolton, Graham Shorrocks wrote

| “ | I have personally known those who would avoid, or could never enjoy, a conversation with a stranger, because they were literally too ashamed to open their mouths. It has been drummed into people—often in school, and certainly in society at large—that dialect speech is incorrect, impure, vulgar, clumsy, ugly, careless, shoddy, ignorant, and altogether inferior. Furthermore, the particularly close link in recent English society between speech, especially accents, and social class and values has made local dialect a hindrance to upward social mobility.'[7] | ” |

The three largest recognisable dialect groups in England are Southern English dialects, Midlands English dialects and Northern English dialects. The most prominent isogloss is the foot–strut split, which runs roughly from mid-Shropshire (on the Welsh border) to south of Birmingham and then to the Wash. South of the isogloss (the Midlands and Southern dialects), the Middle English phoneme /ʊ/ split into /ʌ/ (as in cut, strut) and /ʊ/ (put, foot); this change did not occur north of the Isogloss.

The accent of English English best known outside the United Kingdom is that of Received Pronunciation (RP),[citation needed] though it is used by only a small minority of speakers in England.[8] Until recently, RP was widely considered to be more typical of educated speakers than other accents. It was referred to by some as the Queen's (or King's) English, an 'Oxford accent' or even 'BBC English' (because for many years of broadcasting it was rare to hear any other accent on the BBC). These terms, however, do not refer only to accent features but also to grammar and vocabulary, as explained in Received Pronunciation. Since the 1960s regional accents have become increasingly accepted in mainstream media, and are frequently heard on radio and television. The Oxford English Dictionary gives RP pronunciations for each word, as do most other English dictionaries published in Britain.

Most native English speakers can tell the general region in England that a speaker comes from, and experts or locals may be able to narrow this down to within a few miles. Historically, such differences could be a major impediment to understanding between people from different areas. There are also many cases where a large city has a very different accent from the rural area around it (e.g. Bristol and Avon, Hull and the East Riding, Liverpool and Lancashire). But modern communications and mass media have reduced these differences in some parts of the country.[9][10] Speakers may also change their pronunciation and vocabulary, particularly towards Received Pronunciation and Standard English when in public.

British Isles varieties of English, including English English, are discussed in John C. Wells (1982). Some of the features of English English are that:

- Most versions of this dialect have non-rhotic pronunciation, meaning that [r] is not pronounced in syllable coda position. Non-rhoticity is also found elsewhere in the English-speaking world, including in Australian English, New Zealand English, South African English, New England English, New York City English,[11] and older dialects of Southern American English, as well as most non-native varieties spoken throughout the Commonwealth of Nations.[12][verification needed] Rhotic accents exist in the West Country, parts of Lancashire, the far north of England and in the town of Corby, both of which have a large Scottish influence on their speech.

- As noted above, Northern versions of the dialect lack the foot–strut split, so that there is no distinction between /ʊ/ and /ʌ/, making put and putt homophones as /pʊt/.

- In the Southern varieties, words like bath, cast, dance, fast, after, castle, grass etc. are pronounced with the long vowel found in calm (that is, [ɑː] or a similar vowel) while in the Midlands and Northern varieties they are pronounced with the same vowel as trap or cat, usually [a]. For more details see Trap–bath split. There are some areas of the West Country that use [aː] in both the TRAP and BATH sets. The Bristol area, although in the south of England, uses the short [a] in BATH.[13]

- Many varieties undergo h-dropping, making harm and arm homophones. This is a feature of working-class accents across most of England, but was traditionally stigmatised (a fact the comedy musical My Fair Lady was quick to exploit) but less so now.[14] This was geographically widespread, but the linguist A.C.Gimson stated that it did not extend to the far north, nor to East Anglia, Essex, Wiltshire or Somerset.[15] In the past, working-class people were often unsure where an h ought to be pronounced, and, when attempting to speak 'properly', would often preface any word that began with a vowel with an h (e.g. 'henormous' instead of enormous, 'hicicles' instead of icicles); this was referred to as the 'hypercorrect h' in the Survey of English Dialects, and is also referenced in literature (e.g. the policeman in Danny the Champion of the World).

- A glottal stop for intervocalic /t/ is now common amongst younger speakers across the country; it was originally confined to some areas of the south-east and East Anglia.[citation needed]

- The distinction between /w/ and /hw/ in wine and whine is lost, 'wh' being pronounced consistently as /w/.

- Most varieties have the horse–hoarse merger. However some northern accents retain the distinction, pronouncing pairs of words like for/four, horse/hoarse and morning/mourning differently.[16]

- The consonant clusters /sj/, /zj/, and /lj/ in suit, Zeus, and lute are preserved by some.

- Many Southern varieties have the bad–lad split, so that bad/bæːd/ and lad/læd/ do not rhyme.

- In most of the eastern half of England, plurals and past participle endings which are pronounced /ɪz/ and /ɪd/ (with the vowel of kit) in RP may be pronounced with a schwa/ə/. This can be found as far north as Wakefield and as far south as Essex. This is unusual in being an east-west division in pronunciation when English dialects generally divide between north and south. Another east-west division involves the rhotic [r]; it can be heard in the speech of country folk (particularly the elder), more or less west of the course of the Roman era road known as Watling Street (the modern A5), which at one time divided King Alfred's Wessex and English Mercia from the Danish kingdoms in the east. The rhotic [r] is rarely found in the east.

- Sporadically, miscellaneous items of generally obsolete vocabulary survive: come in the past tense rather than came; the use of thou and/or ye for you.

Change over time[edit]

There has been academic interest in dialects since the late 19th century. The main works are On Early English Pronunciation by A.J. Ellis, English Dialect Grammar by Joseph Wright, and the English Dialect Dictionary also by Joseph Wright. The Dialect Test was developed by Joseph Wright so he could hear the differences of the vowel sounds of a dialect by listening to different people reading the same short passage of text.

In the 1950s and 1960s the Survey of English Dialects was undertaken to preserve a record of the traditional spectrum of rural dialects that merged into each other. The traditional picture was that there would be a few changes in lexicon and pronunciation every couple of miles, but that there would be no sharp borders between completely different ways of speaking. Within a county, the accents of the different towns and villages would drift gradually so that residents of bordering areas sounded more similar to those in neighbouring counties.

Because of greater social mobility and the teaching of 'Standard English' in secondary schools, this model is no longer very accurate. There are some English counties in which there is little change in accent/dialect, and people are more likely to categorise their accent by a region or county than by their town or village. As agriculture became less prominent, many rural dialects were lost. Some urban dialects have also declined; for example, traditional Bradford dialect is now quite rare in the city, and call centres have seen Bradford as a useful location for the very fact there is a lack of dialect in potential employees.[17][18] Some call centres state that they were attracted to Bradford because it has a regional accent which is relatively easy to understand.[19] But working in the opposite direction concentrations of migration may cause a town or area to develop its own accent. The two most famous examples are Liverpool and Corby. Liverpool's dialect is influenced heavily by Irish and Welsh, and it sounds completely different from surrounding areas of Lancashire. Corby's dialect is influenced heavily by Scots, and it sounds completely different from the rest of Northamptonshire. The Voices 2006 survey found that the various ethnic minorities that have settled in large populations in parts of Britain develop their own specific dialects. For example, Asian may have an Oriental influence on their accent so sometimes urban dialects are now just as easily identifiable as rural dialects, even if they are not from South Asia. In the traditional view, urban speech was just seen as a watered-down version of that of the surrounding rural area. Historically, rural areas had much more stable demographics than urban areas, but there is now only a small difference. It has probably never been true since the Industrial Revolution caused an enormous influx to cities from rural areas.

Overview of regional accents[edit]

According to dialectologist Peter Trudgill, the major regional English accents of modern England can be divided on the basis on the following basic features; the word columns each represent the pronunciation of one italicised word in the sentence 'Very few cars made it up the long hill'.[20] An additional feature—the absence or presence of a trap-bath split—is also represented under the 'path' column (so that the sentence could be rendered 'Very few cars made it up the path of the long hill').

| Accent Name | Trudgill's Accent Region | Strongest Centre | very | few | cars | made | up | path | long | hill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geordie | Northeast | Newcastle/Sunderland | /i/ | /juː/ | [ɒː] | [eː] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋ/ | [hɪl] |

| Yorkshire | Central and Lower North | Leeds/Bradford | /ɪ/ | /juː/ | [äː] | [eː] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋ/ | [ɪl] |

| Lancashire(traditional) | Central Lancashire | Rossendale | /ɪ/ | /juː/ | [aːɹ] [note 1] | [eː] | /ʊ / | /æ/ [a] | /ŋg/ | [ɪl] |

| Scouse | Merseyside | Liverpool | /i/ | /juː/ | [äː] | [eɪ] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋg/ | [ɪl] |

| Manchester | Northwest Midlands | Manchester/Salford | /ɪ/ | /juː/ | [äː] | [eɪ] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋg/ | [ɪl] |

| Brummie | West Midlands | Birmingham | /i/ | /juː/ | [ɑː] | [ʌɪ] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋg/ | [ɪl] |

| East Midlands | East, North, and South Midlands | Lincoln | /i/ [note 2] | /juː/ [note 3] | [ɑː] | [eɪ] [note 4] | /ʊ/ | /æ/ [a] | /ŋ/ | [ɪl] [note 5] |

| West Country | Southwest | Bristol/Plymouth | /i/ | /juː/ | [ɑːɹ] | [eɪ] [note 6] | /ʌ/ | /æ/ [æ] | /ŋ/ | [ɪl] [note 7] |

| East Anglian(traditional) | East Anglia | traditional Norfolk/Suffolk | /i/ | /uː/ | [aː] | [æɪ] | /ʌ/ | /æ/ [æ] | /ŋ/ | [(h)ɪl] |

| London/Estuary | Home Counties | Greater London | /i/ | /juː/ | [ɑː] | [eɪ~æɪ] | /ʌ/ | /ɑː/ | /ŋ/ | [ɪo] |

| RP(modern) | /i/ | /juː/ | [ɑː] | [eɪ] | /ʌ/ | /ɑː/ | /ŋ/ | [hɪl] |

Southern England[edit]

In general, Southern English accents are distinguished from Northern English accents primarily by not using the short a in words such as 'bath'. In the south-east, the broad A is normally used before a /f/, /s/ or /θ/: words such as 'cast' and 'bath' are pronounced /kɑːst/, /bɑːθ/ rather than /kæst/, /bæθ/. This sometimes occurs before /nd/: it is used in 'command' and 'demand' but not in 'brand' or 'grand'.

In the south-west, an /aː/ sound in used in these words but also in words that take /æ/ in RP; there is no trap–bath split but both are pronounced with an extended fronted vowel.[21] Bristol is an exception to the bath-broadening rule: it uses /a/ in the trap and bath sets, just as is the case in the North and the Midlands.[22]

Accents originally from the upper class speech of the London–Oxford–Cambridge triangle are particularly notable as the basis for Received Pronunciation.

Southern English accents have three main historical influences:

- London accent, Cockney in particular

- Received Pronunciation

- Southern rural accents (such as West Country, Kent and East Anglian)

Relatively recently, the first two have increasingly influenced southern accents outside London via social class mobility and the expansion of London. From some time during the 19th century, middle and upper middle classes began to adopt affectations, including the RP accent, associated with the upper class. In the late 20th and 21st century other social changes, such as middle class RP-speakers forming an increasing component of rural communities, have accentuated the spread of RP. The South East coast accents traditionally have several features in common with the West country; for example, rhoticity and the a: sound in words such as bath, cast, etc. However, the younger generation in the area is more likely to be non-rhotic and use the London/East Anglian A: sound in bath.

After the Second World War, about one million Londoners were relocated to new and expanded towns throughout the south east, bringing with them their distinctive London accent.

During the 19th century distinct dialects of English were recorded in Sussex, Surrey and Kent. These dialects are now extinct or nearly extinct due to improved communications and population movements.

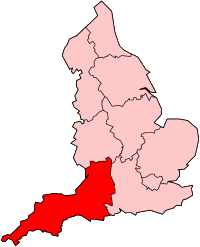

South West England[edit]

The West Country dialects and accents are the English dialects and accents used by much of the indigenous population of South West England, the area popularly known as the West Country.

This region encompasses Bristol, Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset, while Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Wiltshire are usually also included, although the northern and eastern boundaries of the area are hard to define and sometimes even wider areas are encompassed. The West Country accent is said to reflect the pronunciation of the Anglo-Saxons far better than other modern English Dialects.

In the nearby counties of Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, it was possible to encounter comparable accents and, indeed, distinct local dialects until perhaps the 1960s. There is now limited use of such dialects amongst older people in local areas. Although natives of such locations, especially in western parts, can still have West Country influences in their speech, the increased mobility and urbanisation of the population have meant that local Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Hampshire and Isle of Wight dialects (as opposed to accents) are today essentially extinct.

Academically the regional variations are considered to be dialectal forms. The Survey of English Dialects captured manners of speech across the West Country that were just as different from Standard English as anything from the far North. Close proximity has completely different languages such as Cornish, which is a Celtic language related to Welsh, and more closely to Breton.

East Anglia[edit]

Norfolk[edit]

The Norfolk dialect is spoken in the traditional county of Norfolk and areas of north Suffolk. Famous speakers include Keith Skipper.The group FOND (Friends of Norfolk Dialect) was formed to record the county's dialect and to provide advice for TV companies using the dialect in productions.

East Anglian dialect is also spoken in areas of Cambridgeshire. It is characterised by the use of [ei] for /iː/ in FLEECE words.[23]

Midlands[edit]

- As in the North, Midlands accents generally do not use a broad A, so that cast is pronounced [kast] rather than the [kɑːst] pronunciation of most southern accents. The northern limit of the [ɑː] in many words crosses England from mid-Shropshire to The Wash, passing just south of Birmingham.

- The West Midlands accent is often described as having a pronounced nasal quality, the East Midlands accent much less so.

- Old and cold may be pronounced as 'owd' and 'cowd' (rhyming with 'loud' in the West Midlands and 'ode' in the East Midlands), and in the northern Midlands home can become 'wom'.

- Whether Derbyshire should be classed as the West or East Midlands in terms of dialect is debatable. Stanley Ellis, a dialect expert, said in 1985 that it was more like the West Midlands, but it is often grouped with the East and is part of the regionEast Midlands.

- Cheshire, although part of the North-West region, is usually grouped the Midlands for the purpose of accent and dialect.

West Midlands[edit]

- The best known accents in the West Midlands area are the Birmingham accents (see 'Brummie') and the Black Country accent (Yam Yam).

- There is no Ng-coalescence. Cases of the spelling -ing are pronounced as [ɪŋɡ] rather than [ɪŋ]. Wells noted that there were no exceptions to this rule in Stoke-on-Trent, whereas there were for other areas with the [ɪŋɡ] pronunciation, such as Liverpool.[24]

- Dialect verbs are used, for example am for are, ay for is not (related to ain't), bay for are not, bin for am or, emphatically, for are. Hence the following joke dialogue about bay windows: 'What sort of windas am them?' 'They'm bay windas.' 'Well if they bay windas wot bin them?'. There is also humour to be derived from the shop-owner's sign of Mr. 'E. A. Wright' (that is, 'He ay [isn't] right,' a phrase implying someone is saft [soft] in the jed [head]). Saft also may mean silly as in, 'Stop bein' so saft'.

- The Birmingham and Coventry accents are distinct, even though the cities are only 19 miles/30 km apart. Coventry being closer to an East Midlands accent.[citation needed]

- Around Stoke-on-Trent, the short i can sometimes sound rather like ee, as very obvious when hearing a local say it, however this is not always the case as most other words such as 'miss' or 'tip' are still pronounced as normal. The Potteries accent is perhaps the most distinctly 'northern' of the West Midlands accents, given that the urban area around Stoke-on-Trent is close to the Cheshire border.

- Herefordshire and parts of Worcestershire and Shropshire have a rhotic accent[citation needed] somewhat like the West Country, and in some parts mixing with the Welsh accent, particularly when closer to the English/Welsh border.

East Midlands[edit]

- East Midlands accents are generally non-rhotic, instead drawing out their vowels, resulting in the Midlands Drawl, which can to non-natives be mistaken for dry sarcasm.[citation needed]

- The PRICE vowel has a very far back starting-point, and can be realised as [ɑɪ].[25]

- Yod-dropping, as in East Anglia, can be found in some areas[where?], for example new as /nuː/, sounding like 'noo'.

- The u vowel of words like strut is often [ʊ], with no distinction between putt and put. In Lincolnshire, such sounds are even shorter than in the North.

- In Leicester, words with short vowels such as up and last have a northern pronunciation, whereas words with vowels such as down and road sound rather more like a south-eastern accent. The vowel sound at the end of words like border (and the name of the city) is also a distinctive feature.[26]

- Lincolnshire also has a marked north–south split in terms of accent. The north shares many features with Yorkshire, such as the open a sound in 'car' and 'park' or the replacement of take and make with tek and mek. The south of Lincolnshire is close to Received Pronunciation, although it still has a short Northern a in words such as bath.

- Mixing of the words was and were when the other is used in Standard English.

- In Northamptonshire, crossed by the North-South isogloss, residents of the north of the county have an accent similar to that of Leicestershire and those in the south an accent similar to rural Oxfordshire.

- The town of Corby in northern Northamptonshire has an accent with some originally Scottish features, apparently due to immigration of Scottish steelworkers.[27] It is common in Corby for the GOAT set of words to be pronounced with /oː/. This pronunciation is used across Scotland and most of Northern England, but Corby is alone in the Midlands in using it.[28]

Northern England[edit]

There are several accent features which are common to most of the accents of northern England (Wells 1982, section 4.4).

- Northern English tends not to have /ʌ/ (strut, but, etc.) as a separate vowel. Most words that have this vowel in RP are pronounced with /ʊ/ in Northern accents, so that put and putt are homophonous as [pʊt]. But some words with /ʊ/ in RP can have [uː] in the more conservative Northern accents, so that a pair like luck and look may be distinguished as /lʊk/ and /luːk/.

- The accents of Northern England generally do not use a /ɑː/. so cast is pronounced [kast] rather than the [kɑːst] pronunciation of most southern accents. This pronunciation is found in the words that were affected by the trap–bath split.

- For many speakers, the remaining instances of RP /ɑː/ instead becomes [aː]: for example, in the words palm, cart, start, tomato.

- The vowel in dress, test, pet, etc. is slightly more open, transcribed by Wells as [ɛ] rather than [e].

- The 'short a' vowel of cat, trap is normally pronounced [a] rather than the [æ] found in traditional Received Pronunciation and in many forms of American English.

- In most areas, the letter y on the end of words as in happy or city is pronounced [ɪ], like the i in bit, and not [i]. This was considered RP until the 1990s. The longer [i] is found in the far north and in the Merseyside area.

- The phonemes /eɪ/ (as in face) and /oʊ/ (as in goat) are often pronounced as monophthongs (such as [eː] and [oː]). However, the quality of these vowels varies considerably across the region, and this is considered a greater indicator of a speaker's social class than the less stigmatised aspects listed above.

Some dialect words used across the North are listed in extended editions of the Oxford Dictionary with a marker 'North England': for example, the words ginnell and snicket for specific types of alleyway, the word fettle for to organise, or the use of while to mean until. The best-known Northern words are nowt, owt and summat, which are included in most dictionaries. For more localised features, see the following sections.

The 'present historical' is named after the speech of the region, but it is often used in many working class dialects in the south of England too. Instead of saying 'I said to him', users of the rule would say, 'I says to him'. Instead of saying, 'I went up there', they would say, 'I goes up there.'

In the far north of England, the local speech is indistinguishable from Scots. Wells said that northernmost Northumberland 'though politically English is linguistically Scottish'.[29]

Liverpool (Scouse)[edit]

The Liverpool accent, known as Scouse colloquially, is quite different from the accent of surrounding Lancashire. This is because Liverpool has had many immigrants in recent centuries, particularly of Irish people. Irish influences on Scouse speech include the pronunciation of unstressed 'my' as 'me', and the pronunciation of 'th' sounds like 't' or 'd' (although they remain distinct as dental /t̪//d̪/). Other features include the pronunciation of non-initial /k/ as [x], and the pronunciation of 'r' as a tap /ɾ/.

Yorkshire[edit]

Wuthering Heights is one of the few classic works of English literature to contain a substantial amount of dialect. Set in Haworth, the servant Joseph speaks in the traditional dialect of the area, which many modern readers struggle to understand. This dialect was still spoken around Haworth until the late 1970s, but there is now only a minority of it still in everyday use.[30]To hear this old dialect spoken it is necessary to attend a cattle market at Skipton, Otley, Settle or similar places where older farmers from deep in the dales can be heard speaking in what can be baffling dialect to many southerners.

Teesside[edit]

The accents for Teesside are sometimes grouped with Yorkshire and sometimes grouped with the North-East of England, for they share characteristics with both. As this urban area grew in the early 20th century, there are fewer dialect words that date back to older forms of English; Teesside speak is the sort of modern dialect that Peter Trudgill identified in his 'The Dialects of England'. There is a Lower Tees Dialect group.[31] A recent study found that most people from Middlesbrough do not consider their accent to be 'Yorkshire', but that they are less hostile to being grouped with Yorkshire than to being grouped with the Geordie accent.[32]Intriguingly, speakers from Middlesbrough are occasionally mistaken for speakers from Liverpool[33] as they share many of the same characteristics. It is thought the occasional similarities between the Middlesbrough and Liverpool accent may be due to the high number of Irish migration to both areas during the late 1900s in fact the 1871 census showed Middlesbrough had the second highest proportion of people from Ireland after Liverpool. Some examples of traits that are shared with [most parts of] Yorkshire include:

- H-dropping.

- An /aː/ sound in words such as start, car, park, etc.

- In common with the east coast of Yorkshire, words such as bird, first, nurse, etc. have an [ɛː] sound. It can be written as, baird, fairst, nairse'. [This vowel sound also occurs in Liverpool and Birkenhead].

Examples of traits shared with the North-East include:

- Absence of definite article reduction.

- Glottal stops for /k/, /p/ and /t/ can all occur.

The vowel in 'goat' is an /oː/ sound, as is found in both Durham and rural North Yorkshire. In common with this area of the country, Middlesbrough is a non-rhotic accent.

The vowel in 'face' is pronounced as /eː/, as is commonplace in the North-East of England.

Lancashire[edit]

Cumbria[edit]

- People from the Furness peninsula in south Cumbria tend to have a more Lancashire-orientated accent, whilst the dialect of Barrow-in-Furness itself is a result of migration from the likes of Strathclyde and Tyneside. Barrow grew on the shipbuilding industry during the 19th and 20th centuries, and many families moved from these already well established shipbuilding towns to seek employment in Barrow.

North-East England[edit]

- Dialects in this region are often known as Geordie (for speakers from the Newcastle upon Tyne area) or Mackem (for speakers from the Sunderland area). The dialects across the region are broadly similar however some differences do exist. For example, with words ending -re/-er, such as culture and father, the end syllable is pronounced by a Newcastle native as a short 'a', such as in 'fat' and 'back', therefore producing 'cultcha' and 'fatha' for 'culture' and 'father' respectively. The Sunderland area would pronounce the syllable much more closely to that of other accents. Similarly, Geordies pronounce 'make' in line with standard English: to rhyme with take. However, a Mackem would pronounce 'make' to rhyme with 'mack' or 'tack' (hence the origin of the term Mackem). For other differences, see the respective articles. For an explanation of the traditional dialects of the mining areas of County Durham and Northumberland see Pitmatic.

- A feature of the North East accent, shared with Scots and Irish English, is the pronunciation of the consonant cluster -lm in coda position. As an example, 'film' is pronounced as 'fillum'. Another of these features which are shared with Scots is the use of the word 'Aye', pronounced like 'I', its meaning is yes.

Examples of accents used by public figures[edit]

- Received Pronunciation (RP): The Queen's accent has changed slightly over the years but she still speaks a conservative form of RP.[34][35]Margaret Thatcher, Tony Benn and Noël Coward are examples of old-fashioned RP speakers, whereas David Cameron, Boris Johnson, John Cleese and David Dimbleby are examples of contemporary RP.

- Berkshire (a southern rural accent): poet Pam Ayres is from Stanford in the Vale, which belonged to Berkshire until the boundary changes of 1974.

- Derby: actor Jack O'Connell.[36]

- Hampshire (a southern rural accent): the late John Arlott, sports presenter and gardener Charlie Dimmock.

- Essex (Estuary): very strongly noticeable in YouTuberLukeIsNotSexy. Emma Blackery used to speak in a more regionally Essex dialect, but as of early 2018 has mostly transitioned into Modern RP, with subtle Americanization.

- Hertfordshire: comedian and writer Robert Newman

- Lancashire: comedian Peter Kay, McFly singer and guitarist Danny Jones and BBC Radio 1 DJ Vernon Kay as well as Bernard Wrigley have degrees of broad Bolton accents. The actress, Michelle Holmes, has a Rochdale accent, which is similar to the western fringe of Yorkshire and she has featured mostly in Yorkshire dramas. Julie Hesmondhalgh, Vicky Entwistle and Julia Haworth, actresses in the soap opera Coronation Street, have East Lancashire accents which have a slightly different intonation and rhythm and also feature variable rhoticity.

- Leicester: The band Kasabian have Leicester accents.

- London: old recordings by Petula Clark, Julie Andrews, the Rolling Stones, and The Who (although many of these contain affected patterns). For clear examples, see actor Stanley Holloway (Eliza Doolittle's father in My Fair Lady), or footballerDavid Beckham.

- Cockney: the actors Bob Hoskins, Michael Caine. Ray Winstone has quite an old-fashioned Cockney accent, and his replacement of an initial /r/ with a /w/ has been stigmatised. More examples can be heard in the movies Snatch and Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels. The Sex Pistols had Cockney accents, with Steve Jones having the strongest.

- Mockney: used by Guy Ritchie and many musicians, it is a variant of the London regional accent characterised by a non-standard mixture of linguistic and social class characteristics.

- West London: the journalist Janet Street Porter.

- Estuary: athlete Sally Gunnell, the model Jordan (Katie Price).

- Manchester: Oasis members Liam and Noel Gallagher, Herman's Hermits, actor Dominic Monaghan, broadcaster/podcaster Karl Pilkington, physicist Brian Cox (physicist).

- Merseyside (Scouse)

- Liverpool: Liverpool footballers Steven Gerrard and Jamie Carragher are often cited as having particularly strong scouse accents.[citation needed] Recordings by The Beatles (George Harrison's accent was the strongest of the four), Gerry & The Pacemakers, Echo and the Bunnymen. Also the singer Cilla Black and the actors Craig Charles and Ricky Tomlinson. The British soap Brookside was set in Liverpool so the majority of the cast, including Philip Olivier and Jennifer Ellison, had scouse accents.

- St Helens: Comedian Johnny Vegas. The comedy band the Lancashire Hotpots sing in a traditional rhotic St Helens accent.

- The Wirral: Comedian and TV presenter Paul O'Grady alias Lily Savage is from Birkenhead, pop singer Pete Burns of Dead or Alive is from the model villagePort Sunlight.

- Nottingham: boxer Carl Froch.

- Salford: actor Christopher Eccleston, bands Happy Mondays and New Order.

- Stoke-on-Trent or The Potteries: pop star Robbie Williams, TV presenter Anthea Turner, ex pop star and TV presenter Jonathan Wilkes.

- Sunderland (Mackem): the accent of the rock group The Futureheads is easily detected on recordings and live performances and ex-footballer Chris Waddle.

- Tyneside (Geordie): former Cabinet members Alan Milburn MP and Nick Brown MP, the actors Robson Green and Tim Healy, the footballer Alan Shearer, actor and singer Jimmy Nail, rock singer Brian Johnson, singer Cheryl, television personalities Ant and Dec, Donna Air and Jayne Middlemiss.

- West Country: The Vicar of Dibley was set in Oxfordshire, and many of the characters had West Country accents.[clarification needed]

- Bristol: Professor Colin Pillinger of the Beagle 2 project, comedy writer, actor, radio DJ and director Stephen Merchant. Presenter and Comedian Justin Lee Collins.

- Gloucestershire: Laurie Lee, ruralist

- West Midlands: Phil Drabble, presenter of One Man and His Dog.

- Birmingham (Brummie): the rock musician Ozzy Osbourne (although he sometimes Americanises his speech), Jasper Carrot and Rob Halford. See Brummie for more examples.

- Coventry: the actor Clive Owen, in the films Sin City and King Arthur. Singer-songwriter Terry Hall, lead vocalist with The Specials.

- Yorkshire:

- Barnsley: in the 1969 film Kes, the lead characters, David Bradley and Freddie Fletcher, both have very broad Barnsley accents, which are less likely to be heard nowadays. Coronation Street actress Katherine Kelly, Sam Nixon from Pop Idol 2003, Top of the Pops Saturday and Reloaded and Level Up also has a Barnsley accent. Also, chat show host Michael Parkinson and ex-union leader Arthur Scargill have slightly reduced Barnsley accents.

- Bradford: singers Gareth Gates, Zayn Malik of One Direction and Kimberley Walsh of Girls Aloud. In Rita, Sue and Bob Too, Bob has a Bradford accent whilst Rita and Sue sound more like Lancashire.

- Hemsworth: cricketer Geoffrey Boycott has an accent similar to those found in many old coal-mining towns

- Holme Valley: Actors Peter Sallis and Bill Owen of Last of the Summer Wine and Sallis in Wallace and Gromit (although Sallis and Owen themselves were both Londoners)

- Leeds: Melanie Brown of the Spice Girls and Beverley Callard who plays Liz McDonald in Coronation Street, singer Corinne Bailey Rae, the band Kaiser Chiefs, model Nell McAndrew, actress Angela Griffin, Radio DJ Chris Moyles, Comedian Leigh Francis alias Keith Lemon

- Wakefield, singer and actress Jane McDonald, Hollyoaks actress Claire Cooper, actor Reece Dinsdale, Coronation StreetHelen Worth, the band the Cribs

- Scarborough: the film Little Voice

- Sheffield: Ken Loach's 1977 film The Price of Coal was filmed almost entirely in the traditional dialect of the Sheffield-Rotherham area, but this variety of speech is receding. For examples of less marked Sheffield speech, see Sean Bean, the band Pulp, the film The Full Monty and the band Arctic Monkeys.

Regional English accents in the media[edit]

The Archers has had characters with a variety of different West Country accents (see Mummerset).

The shows of Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement have often included a variety of regional accents, the most notable being Auf Wiedersehen Pet about Geordie men in Germany. Porridge featured London and Cumberland accents, and The Likely Lads featured north east England.

The programmes of Carla Lane such as The Liver Birds and Bread featured Scouse accents.

In the 2005 version of the science fiction programme Doctor Who, various Londoners wonder why the Doctor (played byChristopher Eccleston), an alien, sounds as if he comes from the North. Eccleston used his own Salford accent in the role; the Doctor's usual response is 'Lots of planets have a North!' Other accents in the same series include Cockney (used by actress Billie Piper) and Estuary (used by actress Catherine Tate).

A television reality programme Rock School was set in Suffolk in its second series, providing lots of examples of the Suffolk dialect.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^English, a. and n. (2nd ed.). The Oxford English Dictionary. 1989.

- ^Trudgill (2002), p 2.

- ^Tom McArthur, The Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language. Retrieved via encyclopedia.com.

- ^Todd, Loreto; Hancock, Ian (1990). International English Usage. London. ISBN9780415051026.

- ^According to Tom McArthur in the Oxford Guide to World English (p. 45)

- ^Bernard Shaw, George (1916), 'Preface', Pygmalion, A Professor of Phonetics, retrieved 20 April 2009

- ^Shorrocks, Graham (1998). A Grammar of the Dialect of the Bolton Area. Pt. 1: Introduction; phonology. Bamberger Beiträge zur englischen Sprachwissenschaft; Bd. 41. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 90. ISBN3-631-33066-9.

- ^About 2% of Britons speak RP (Learning: Language & Literature: Sounds Familiar?: Case studies: Received PronunciationBritish Library)

- ^Voices 2005: Accent – a great leveller? BBC 15 August 2005. Interview with Professor Paul Kerswill who stated 'The difference between regional accents is getting less with time.'

- ^Liverpool Journal; Baffling Scouse Is Spoken Here, So Bring a Sensa YumaInternational Herald Tribune, 15 March 2005. 'While most regional accents in England are growing a touch less pronounced in this age of high-speed travel and 600-channel satellite systems, it seems that the Liverpool accent is boldly growing thicker. .. migrating London accents are blamed for the slight changes in regional accents over the past few decades. .. That said, the curator of English accents and dialects at the British Library said the Northeast accents, from places like Northumberland and Tyneside, were also going stronger.'

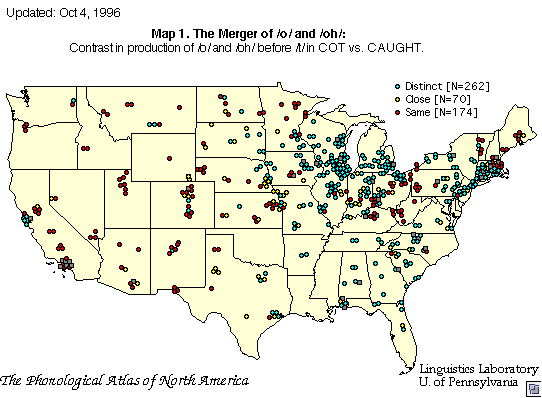

- ^Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. chpt. 17.

- ^Trudgill and Hannah, p 138.

- ^p.348-349, Accents of English 2 John C Wells, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992

- ^Trask (1999), pp104–106.

- ^A.C. Gimson in Collins English Dictionary, 1979, page xxiv

- ^Wells 1982, section 4.4.

- ^'By 'eck! Bratford-speak is dyin' out'. Bradford Telegraph & Argus. 5 April 2004. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2007.Cite uses deprecated parameter

dead-url=(help) - ^'Does tha kno't old way o' callin'?'. BBC News. 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^Mahony, GV (January 2001). 'Race relations in Bradford'(PDF). GV Mahony: 8. Retrieved 12 September 2007.Cite journal requires

journal=(help) - ^Ihalainen, Ossi (1992). 'The Dialects of England since 1776'. In The Cambridge History of the English language. Vol. 5, English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development, ed. Robert Burchfield, p. 255-258. Cambridge University Press.

- ^John C Wells, Accents of English, Cambridge, 1983, p.352

- ^John C Wells, Accents of English, Cambridge, 1983, p.348

- ^John Wells in Peter Trudgill ed., Language in the British Isles, page 62, Cambridge University Press, 1984

- ^Wells in Trudgill ed., Language in the British Isles, page 58, Cambridge University Press, 1984

- ^Hughes, Trudgill & Watts ed., English accents and dialects: an introduction to social and regional varieties of English in the British Isles, chapter on Leicester's speech, Hodder Arnold, 2005

- ^'Voices - The Voices Recordings'. BBC. 6 July 1975. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2013.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 27 July 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2005.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^Language in the British Isles, page 67, ed. David Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2007

- ^Accents of English, Cambridge, 1983, p.351

- ^K.M. Petyt, Emily Bronte and the Haworth Dialect, Hudson History, Settle, 2001.

- ^Wood, Vic (2007). 'TeesSpeak: Dialect of the Lower Tees Valley'. This is the North East. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.Cite uses deprecated parameter

dead-url=(help) - ^Llamas, Carmen. 'Middlesbrough English: Convergent and divergent trends in a 'Par of Britain with no identity''(PDF). University of Leeds. Retrieved 12 September 2007.Cite journal requires

journal=(help) - ^'The shifting sand(-shoes) of linguistic identity in Teesside - Sound and vision blog'. Blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^'The Queen's English'. Phon.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^'Language Log: Happy-tensing and coal in sex'. Itre.cis.upenn.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^'Jack O'Connell's dilemma over accent'. Breaking News. Breaking News. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

References[edit]

- ^This traditional feature of rhoticity in Lancashire is increasingly giving way to non-rhoticity: Beal, Joan (2004). 'English dialects in the North of England: phonology'. A Handbook of Varieties of English (pp. 113-133). Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 127.

- ^[ɪ] defines the Central Midlands (centred on Nottingham and Derby).

- ^[uː] defines the East Midlands (centred on Leicester and Rutland) and partly defines the South Midlands (centred on Northampton and Bedford).

- ^[eː] defines South Humberside or North Lincolnshire (centred on Scunthorpe).

- ^[ɪo] defines the South Midlands (centred on Northampton and Bedford).

- ^[eː] defines the Lower Southwest (Cornwall and Devon).

- ^[ɪo] defines the Central Southwest.

- Peters, Pam (2004). The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-62181-X.

- McArthur, Tom (2002). Oxford Guide to World English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-19-866248-3 hardback, ISBN0-19-860771-7 paperback.

- Trask, Larry (1999). Language: The Basics, 2nd edition. London: Routledge. ISBN0-415-20089-X.

- Trudgill, Peter (1984). Language in the British Isles. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-28409-0.

- Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. (2002). International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English, 4th ed. London: Arnold. ISBN0-340-80834-9.

- Wells, J. C. (1982). Accents of English 2: The British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-28540-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Partridge, A. C. (1969). Tudor to Augustan English: a Study in Syntax and Style, from Caxton to Johnson, in series, The Language Library. London: A. Deutsch. 242 p. SBN 233-96092-9

External links[edit]

- British National Corpus. (Official website for the BNC.)

- English Accents and Dialects: searchable free-access archive of 681 English English speech samples, wma format with linguistic commentary including phonetic transcriptions in X-SAMPA, British Library Collect Britain website.

- 'European Commission English Style Guide'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 December 2010.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help)(621 KB). (Advocates -ise spellings.) - For the Yorkshire dialect, see https://web.archive.org/web/20070716060325/http://www.yorksj.ac.uk/dialect/

H-dropping or aitch-dropping is the deletion of the voiceless glottal fricative or 'H sound', [h]. The phenomenon is common in many dialects of English, and is also found in certain other languages, either as a purely historical development or as a contemporary difference between dialects. Although common in most regions of England and in some other English-speaking countries, H-dropping is often stigmatized and perceived as a sign of careless or uneducated speech.[citation needed]

The reverse phenomenon, H-insertion or H-adding, is found in certain situations, sometimes as a hypercorrection by H-dropping speakers, and sometimes as a spelling pronunciation or out of perceived etymological correctness. A particular example of this is the spread of 'haitch' for 'aitch'.

- 1In English

- 1.2Contemporary H-dropping

In English[edit]

Historical /h/-loss[edit]

In Old English phonology, the sounds [h], [x], and [ç] (described respectively as glottal, velar and palatal voiceless fricatives) are taken to be allophones of a single phoneme /h/. The [h] sound appeared at the start of a syllable, either alone or in a cluster with another consonant. The other two sounds were used in the syllable coda ([x] after back vowels and [ç] after front vowels).

The instances of /h/ in coda position were lost during the Middle English and Early Modern English periods, although they are still reflected in the spelling of words such as taught (now pronounced like taut) and weight (now pronounced in most accents like wait). Most of the initial clusters involving /h/ also disappeared (see H-cluster reductions). As a result, in the standard varieties of Modern English, the only position in which /h/ can occur is at the start of a syllable, either alone (as in hat, house, behind, etc.), in the cluster /hj/ (as in huge), or (for a minority of speakers) in the cluster /hw/ (as in whine if pronounced differently from wine). The usual realizations of the latter two clusters are [ç] and [ʍ] (see English phonology).

Contemporary H-dropping[edit]

The phenomenon of H-dropping considered as a feature of contemporary English is the omission, in certain accents and dialects, of this syllable-initial /h/, either alone or in the cluster /hj/. (For the cluster /hw/ and its reduction, see Pronunciation of English ⟨wh⟩.)

Description[edit]

H-dropping, in certain accents and dialects of Modern English, causes words like harm, heat, and behind to be pronounced arm, eat, and be-ind (though in some dialects an [h] may appear in behind to prevent hiatus – see below).

Cases of H-dropping occur in all English dialects in the weak forms of function words like he, him, her, his, had, and have. The pronoun it is a product of historical H-dropping – the older hit survives as an emphatic form in a few dialects such as Southern American English, and in the Scots language.[1] Because the /h/ of unstressed have is usually dropped, the word is usually pronounced /əv/ in phrases like should have, would have, and could have. These can be spelled out in informal writing as 'should've', 'would've', and 'could've'. Because /əv/ is also the weak form of the word of, these words are often misspelled as should of, would of and could of.

History[edit]

There is evidence of h-dropping in texts from the 13th century and later. It may originally have arisen through contact with the Norman language, where h-dropping also occurred. Puns which rely on the possible omission of the /h/ sound can be found in works by William Shakespeare and in other Elizabethan era dramas. It is suggested that the phenomenon probably spread from the middle to the lower orders of society, first taking hold in urban centers. It started to become stigmatized, being seen as a sign of poor education, in the 16th or 17th century.[2][3]

Geographical distribution[edit]

H-dropping occurs (variably) in most of the dialects of the English language in England and Welsh English, including Cockney, West Country English, West Midlands English (including Brummie), most of northern England (including Yorkshire and Lancashire), and Cardiff English.[5] It is not generally found in Scottish English. It is also typically absent in certain regions of England, including Northumberland and East Anglia.

H-dropping also occurs in General Australian, most of Jamaican English, and perhaps in other Caribbean English (including some of The Bahamas). It is not generally found in North American English, although it has been reported in Newfoundland (outside the Avalon Peninsula).[6] However, dropping of /h/ from the cluster /hj/ (so that human is pronounced /'juːmən/) is found in some American dialects, as well as in parts of Ireland – see reduction of /hj/.

Social distribution and stigmatization[edit]

H-dropping, in the countries and regions in which it is prevalent, occurs mainly in working-class accents. Studies have shown it to be significantly more frequent in lower than in higher social groups. It is not a feature of RP (the prestige accent of England), or even of 'Near-RP', a variant of RP that includes some regional features.[7] This does not apply, however, to the dropping of /h/ in weak forms of words like his and her, as described above – this is normal in all varieties of English.

H-dropping in English is widely stigmatized, being perceived as a sign of poor or uneducated speech, and discouraged by schoolteachers. John Wells writes that it seems to be 'the single most powerful pronunciation shibboleth in England.'[8]

Use and status of the H-sound in H-dropping dialects[edit]

In fully H-dropping dialects, that is, in dialects without a phonemic /h/, the sound [h] may still occur but with uses other than distinguishing words. An epenthetic[h] may be used to avoid hiatus, so that for example the egg is pronounced the hegg. It may also be used when any vowel-initial word is emphasized, so that horse/ˈɔːs/ (assuming the dialect is also non-rhotic) and ass/ˈæs/ may be pronounced [ˈˈhɔːs] and [ˈˈhæs] in emphatic utterances. That is, [h] has become an allophone of the zero onset in these dialects.

For many H-dropping speakers, however, a phonological /h/ appears to be present, even if it is not usually realized – that is, they know which words 'should' have an /h/, and have a greater tendency to pronounce an [h] in those words than in other words beginning with a vowel. Insertion of [h] may occur as a means of emphasis, as noted above, and also as a response to the formality of a situation.[9]Sandhi phenomena may also indicate a speaker's awareness of the presence of an /h/ – for example, some speakers might say 'a edge' (rather than 'an edge') for a hedge, and might omit the linking R before an initial vowel resulting from a dropped H.

It is likely that the phonemic system of children in H-dropping areas lacks an /h/ entirely, but that social and educational pressures lead to the incorporation of an (inconsistently realized) /h/ into the system by the time of adulthood.[10]

H-insertion[edit]

The opposite of H-dropping, called H-insertion or H-adding, sometimes occurs as a hypercorrection in typically H-dropping accents of English. It is commonly noted in literature from late Victorian times to the early 20th century that some lower-class people consistently drop h in words that should have it, while adding h to words that should not have it. An example from the musical My Fair Lady is, 'In 'Artford, 'Ereford, and 'Ampshire, 'urricanes 'ardly hever 'appen'. Another is in C. S. Lewis' The Magician's Nephew: 'Three cheers for the Hempress of Colney 'Atch'. In practice, however, it would appear that h-adding is more of a stylistic prosodic effect, being found on some words receiving particular emphasis, regardless of whether those words are h-initial or vowel-initial in the standard language.

Some English words borrowed from French begin with the letter ⟨h⟩ but not with the sound /h/. Examples include hour, heir, hono(u)r and honest. In some cases, spelling pronunciation has introduced the sound /h/ into such words, as in humble, hotel and (for most speakers) historic. Spelling pronunciation has also added /h/ to the British English pronunciation of herb, /hɜːb/, while American English retains the older pronunciation /ɜrb/. Etymology may also serve as a motivation for H-addition, as in the words horrible, habit and harmony; these were borrowed into Middle English from French without an /h/ (orribel, abit, armonie), but all three derive from Latin words with an /h/ and would later acquire an /h/ in English as an etymological 'correction'.[11] The name of the letter H itself, 'aitch', is subject to H-insertion in some dialects, where it is pronounced 'haitch'. In Hiberno-English, 'haitch' is considered standard.[12]

List of homophones resulting from H-dropping[edit]

The following is a list of some pairs of English words which may become homophones when H-dropping occurs. (To view the list, click 'show'.) See also the list of H-dropping homophones in Wiktionary.

| /h/ | /∅/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| habit | abbot | ˈæbət | With weak vowel merger. |

| hacked | act | ˈækt | |

| hacks | axe; ax | ˈæks | |

| had | ad | ˈæd | |

| had | add | ˈæd | |

| hail | ail | ˈeɪl | |

| hail | ale | ˈeɪl | With pane-pain merger. |

| Haim | aim | ˈeɪm | |

| hair | air | ˈɛə(r), ˈeɪr | |

| hair | ere | ˈɛə(r) | With pane-pain merger. |

| hair | heir | ˈɛə(r), ˈeɪr | |

| haired | erred | ˈɛə(r)d | With pane-pain merger. |

| Hal | Al | ˈæl | |

| hale | ail | ˈeɪl | With pane-pain merger. |

| hale | ale | ˈeɪl, ˈeːl | |

| hall | all | ˈɔːl | |

| halter | alter | ˈɔːltə(r) | |

| ham | am | ˈæm | |

| hand | and | ˈænd | |

| hanker | anchor | ˈæŋkə(r) | |

| hap | app | ˈæp | |

| hare | air | ˈɛə(r) | With pane-pain merger. |

| hare | ere | ˈɛə(r), ˈeːr | |

| hare | heir | ˈɛə(r) | With pane-pain merger. |

| hark | arc | ˈɑː(r)k | |

| hark | ark | ˈɑː(r)k | |

| harm | arm | ˈɑː(r)m | |

| hart | art; Art | ˈɑː(r)t | |

| has | as | ˈæz | |

| haste | aced | ˈeɪst, ˈeːst | |

| hat | at | ˈæt | |

| hate | ate | ˈeɪt | |

| hate | eight | ˈeɪt | With pane-pain merger and wait-weight merger. |

| haul | all | ˈɔːl | |

| haunt | aunt | ˈɑːnt | With trap-bath split and father-bother merger. |

| hawk | auk | ˈɔːk | |

| hawk | orc | ˈɔːk | In non-rhotic accents. |

| head | Ed | ˈɛd | |

| heady | Eddie | ˈɛdi | |

| heady | eddy | ˈɛdi | |

| heal | eel | ˈiːl | With fleece merger. |

| hear | ear | ˈɪə(r), ˈiːr | |

| heard | erred | ˈɜː(r)d, ˈɛrd | |

| hearing | earing | ˈɪərɪŋ, ˈiːrɪŋ | |

| hearing | earring | ˈɪərɪŋ | |

| heart | art; Art | ˈɑː(r)t | |

| heat | eat | ˈiːt | |

| heathen | even | ˈiːvən | With th-fronting. |

| heather | ever | ˈɛvə(r) | With th-fronting. |

| heave | eve; Eve | ˈiːv | |

| heave | eave | ˈiːv | |

| heaven | Evan | ˈɛvən | |

| heaving | even | ˈiːvən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| hedge | edge | ˈɛdʒ | |

| heel | eel | ˈiːl | |

| heist | iced | ˈaɪst | |

| Helen | Ellen | ˈɛlən | |

| Helena | Eleanor | ˈɛlənə | In non-rhotic accents. |

| Helena | Elena | ˈɛlənə | |

| hell | L; el; ell | ˈɛl | |

| he'll | eel | ˈiːl | |

| helm | elm | ˈɛlm | |

| herd | erred | ˈɜː(r)d, ˈɛrd | |

| here | ear | ˈɪə(r), ˈiːr | |

| heron | Erin | ˈɛrən | With weak vowel merger. |

| herring | Erin | ˈɛrən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| hew | ewe | ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪu | |

| hew | yew | ˈjuː, ˈjɪu | |

| hew | you | ˈjuː | |

| hews | ewes | ˈjuːz, ˈ(j)ɪuz | |

| hews | use | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| hews | yews | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| hex | ex | ˈɛks | |

| hi | aye; ay | ˈaɪ | |

| hi | eye | ˈaɪ | |

| hi | I | ˈaɪ | |

| hid | id | ˈɪd | |

| hide | I'd | ˈaɪd | |

| high | aye; ay | ˈaɪ | |

| high | eye | ˈaɪ | |

| high | I | ˈaɪ | |

| higher | ire | ˈaɪə(r) | |

| hike | Ike | ˈaɪk | |

| hill | ill | ˈɪl | |

| hinky | inky | ˈɪŋki | |

| hire | ire | ˈaɪə(r), ˈaɪr | |

| his | is | ˈɪz | |

| hit | it | ˈɪt | |

| hitch | itch | ˈɪtʃ | |

| hive | I've | ˈaɪv | |

| hoard | awed | ˈɔːd | In non-rhotic accents with horse-hoarse merger. |

| hoard | oared | ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd | |

| hoarder | order | ˈɔː(r)də(r) | With horse-hoarse merger. |

| hocks | ox | ˈɒks | |

| hoe | O | ˈoʊ, ˈoː | |

| hoe | oh | ˈoʊ, ˈoː | |

| hoe | owe | ˈoʊ | With toe-tow merger. |

| hoister | oyster | ˈɔɪstə(r) | |

| hold | old | ˈoʊld | |

| holed | old | ˈoʊld | With toe-tow merger. |

| holly | Olly | ˈɒli | |

| hone | own | ˈoʊn | With toe-tow merger. |

| hop | op | ˈɒp | |

| hopped | opped | ˈɒpt | |

| hopped | opt | ˈɒpt | |

| horde | awed | ˈɔːd | In non-rhotic accents. |

| horde | oared | ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd | |

| horn | awn | ˈɔːn | In non-rhotic accents. |

| horn | on | ˈɔːn | In non-rhotic accents with lot-cloth split. |

| hotter | otter | ˈɒtə(r) | |

| how | ow | ˈaʊ | |

| howl | owl | ˈaʊl | |

| how're | hour | ˈaʊə(r), ˈaʊr | |

| how're | our | ˈaʊə(r), ˈaʊr | |

| Hoyle | oil | ˈɔɪl | |

| hue | ewe | ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪuː | |

| hue | yew | ˈjuː, ˈjɪuː | |

| hue | you | ˈjuː | |

| hues | ewes | ˈjuːz, ˈ(j)ɪuz | |

| hues | use | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| hues | yews | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| Hugh | ewe | ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪuː | |

| Hugh | yew | ˈjuː, ˈjɪuː | |

| Hugh | you | ˈjuː | |

| Hughes | ewes | ˈjuːz, ˈ(j)ɪuz | |

| Hughes | use | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| Hughes | yews | ˈjuːz, ˈjɪuz | |

| hurl | earl | ˈɜː(r)l | With fern-fir-fur merger. |

| Hyde | I'd | ˈaɪd | |

| whore | awe | ˈɔː | In non-rhotic accents with horse-hoarse merger and pour-poor merger. |

| whore | oar | ˈɔː(r), ˈoə(r), ˈoːr | With pour-poor merger. |

| whore | or | ˈɔː(r) | With horse-hoarse merger and pour-poor merger. |

| whore | ore | ˈɔː(r), ˈoə(r), ˈoːr | With pour-poor merger. |

| whored | awed | ˈɔːd | In non-rhotic accents with horse-hoarse merger and pour-poor merger. |

| whored | oared | ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd | With pour-poor merger. |

| who's | ooze | ˈuːz | |

| whose | ooze | ˈuːz |

In other languages[edit]

Processes of H-dropping have occurred in various languages at certain times, and in some cases, they remain as distinguishing features between dialects, as in English. Some Dutch dialects, especially the southern ones, feature H-dropping. The dialects of Zeeland, West and East Flanders, most of Antwerp and Flemish Brabant, and the west of North Brabant have lost /h/ as a phonemic consonant but use [h] to avoid hiatus and to signal emphasis, much as in the H-dropping dialects of English.[13] H-dropping is also found in some North Germanic languages, for instance Elfdalian and the dialect of Roslagen, where it is found already in Old East Norse.

The phoneme /h/ in Ancient Greek, occurring only at the beginnings of words and originally written with the letter H and later as a rough breathing, was lost in the Ionic dialect. It is also not pronounced in Modern Greek.

The phoneme /h/ was lost in Late Latin, the ancestor of the modern Romance languages. Both French and Spanish acquired new initial /h/ in medieval times, but they were later lost in both languages in a 'second round' of H-dropping. (However, some dialects of Spanish have reacquired /h/ from Spanish /x/ and Latin /f/.)

It is hypothesized in the laryngeal theory that the loss of [h] or similar sounds played a role in the early development of the Indo-European languages.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^David D. Murison, The Guid Scots Tongue, Blackwodd 1977, p. 39.

- ^Milroy, J., 'On the Sociolinguistic History of H-dropping in English', in Current topics in English historical linguistics, Odense UP, 1983.

- ^Milroy, L., Authority in Language: Investigating Standard English, Routledge 2002, p. 17.

- ^Upton, C., Widdowson, J.D.A., An Atlas of English Dialects, Routledge 2006, pp. 58–59.

- ^Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2002). The Phonetics of Dutch and English(PDF) (5 ed.). Leiden/Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 290–302.

- ^Wells, J.C., Accents of English, CUP 1982, pp. 564, 568–69, 589, 594, 622.

- ^Wells (1982), pp. 254, 300.

- ^Wells (1982), p. 254

- ^Wells (1982), p. 322.

- ^Wells (1982), p. 254.

- ^'World of words - Oxford Dictionaries Online'. Askoxford.com. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ^''Haitch' or 'aitch'? How do you pronounce 'H'?'. BBC. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ^'h'. Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)